Urate-Lowering Therapy: What It Is, How It Works, and What You Need to Know

When your body makes too much urate-lowering therapy, a medical approach designed to reduce excess uric acid in the blood to prevent gout attacks and joint damage. Also known as uric acid reduction therapy, it’s not just about easing pain—it’s about stopping long-term damage before it starts. High levels of uric acid don’t always cause symptoms, but when they do, they turn into sharp crystals in your joints. That’s gout. And if left unchecked, those crystals can erode bone, form tophi (painful lumps under the skin), and even damage your kidneys.

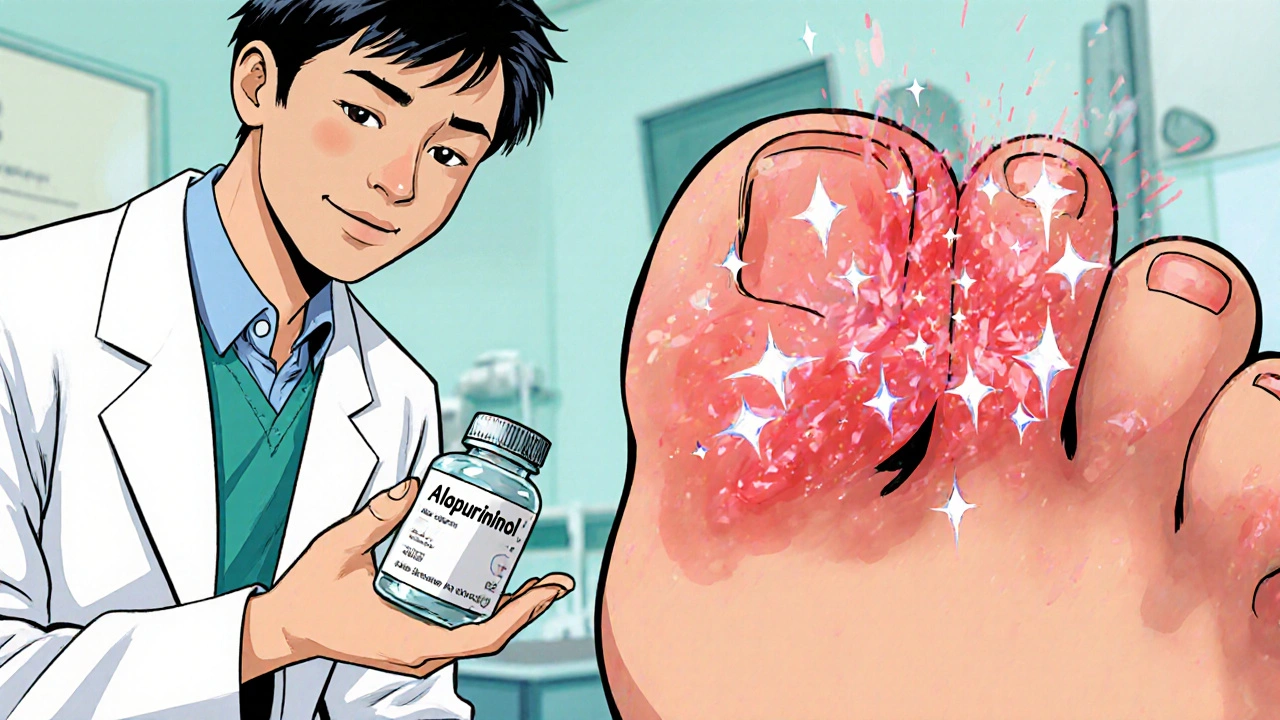

This therapy isn’t a quick fix. It’s a long-term plan, usually started after a person has had more than one gout flare. The goal? Keep serum uric acid below 6 mg/dL. That’s the level where crystals begin to dissolve. The two main drugs used are allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that blocks uric acid production and febuxostat, a newer option for people who can’t tolerate allopurinol. Both work differently than painkillers. They don’t stop a flare once it’s happening—they prevent future ones by changing how your body handles uric acid over time.

People often confuse urate-lowering therapy with treating a gout attack. That’s like taking aspirin for a fever and thinking you’re curing the infection. You need both: fast relief for the flare (like colchicine or NSAIDs), and slow, steady control with urate-lowering therapy to stop it from coming back. It takes months, sometimes years, for crystals to fully dissolve. That’s why sticking with it matters—even if you feel fine. Skipping doses because you’re not in pain is the #1 reason treatment fails.

What you might not realize is that this therapy isn’t just for people with frequent gout. It’s also used in those with kidney stones caused by uric acid, or people on chemotherapy who are at risk of tumor lysis syndrome. Even if you’re not in pain, high uric acid can quietly harm your kidneys. And while diet plays a role—avoiding beer, red meat, and sugary drinks—it rarely lowers uric acid enough on its own. That’s why meds are often necessary.

The posts you’ll find here cover real-world experiences with these drugs, how they interact with other meds like diuretics or aspirin, what side effects to watch for, and how to tell if the treatment is working. You’ll see how patients manage the early stages when flares can actually get worse before they get better. You’ll find tips on monitoring blood levels, adjusting doses, and what to do when your doctor says it’s time to switch. This isn’t theory. It’s what people actually deal with when they start this therapy—and how they make it work.