180-Day Exclusivity and Authorized Generics: Legal Considerations in the U.S. Drug Market

Dec, 4 2025

Dec, 4 2025

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic company to challenge that patent gets a powerful reward: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. This isn’t just a business perk-it’s a legal lifeline built into U.S. drug law. But here’s the twist: while that generic company is enjoying its monopoly, the original brand-name maker can legally launch its own version of the same drug-just without the brand name. This is called an authorized generic. And it’s turning what was meant to be a financial windfall into a competitive free-for-all.

How the 180-Day Exclusivity Rule Was Supposed to Work

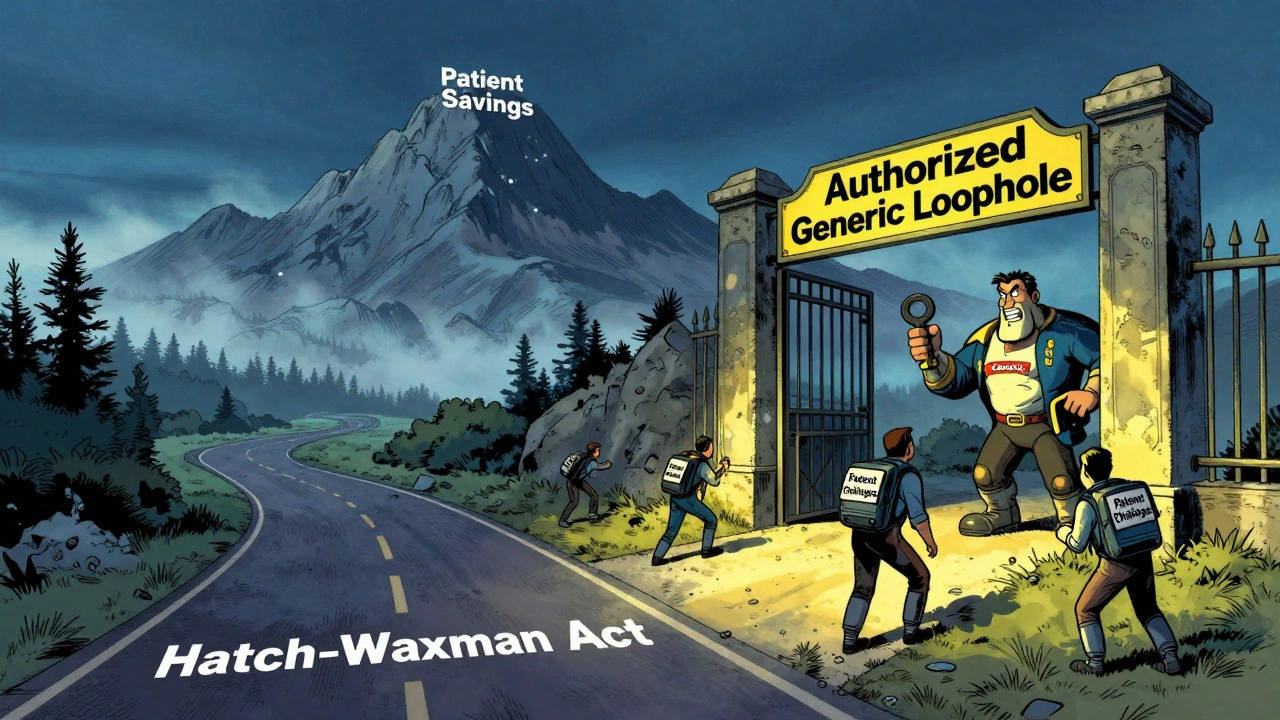

The 180-day exclusivity rule comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was designed to fix a broken system. Before then, brand-name drugs held a monopoly for years, even after patents expired, because no one wanted to spend millions challenging them in court. The law changed that by offering a big prize: if a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification-saying the brand’s patent is invalid or not being infringed-and wins the legal battle, they get 180 days with no competition.This was supposed to be a game-changer. The first generic company could capture nearly all of the market. Prices would drop fast. Patients would save money. And the incentive to take on risky, expensive lawsuits would be strong enough to bring more generics to market.

The math was simple: if you’re the only one selling the generic, you control pricing. You can sell at a discount but still make a huge profit. Some estimates say a single 180-day exclusivity period can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. For a small generic company, that’s life-changing money.

What Is an Authorized Generic-and Why It’s a Problem

An authorized generic isn’t a knockoff. It’s the exact same pill, made by the same company, in the same factory, with the same ingredients. The only difference? No brand name on the box. The brand-name company simply rebrands its own drug as a generic and sells it at a lower price.Here’s the catch: the FDA allows this during the 180-day exclusivity window. That means the company that spent years and millions challenging the patent now has to compete with the very brand it tried to unseat.

Real-world data shows this isn’t theoretical. Between 2005 and 2015, brand-name companies launched authorized generics in about 60% of cases where 180-day exclusivity was granted. When that happens, the first generic’s market share drops from around 80% to just 50%. Revenue losses? Often 30% to 50%.

Take Teva’s case with Eli Lilly’s Humalog insulin. Teva won its patent challenge and launched its generic. Then Lilly rolled out its own authorized version. Teva estimated it lost $287 million in revenue because of it. That’s not an outlier. It’s the new normal.

Legal Gray Zones and Court Battles

The Hatch-Waxman Act never said brand-name companies couldn’t launch authorized generics. It didn’t even mention them. That’s why courts have struggled to rule against them. The law was written for a time when generics were made by separate companies, not by the brand-name manufacturers themselves.The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been pushing back. Between 2010 and 2022, they filed 15 antitrust lawsuits against brand-name companies for allegedly using authorized generics to delay real competition. In their view, this isn’t competition-it’s a loophole. The FTC argues that if the brand can enter the market the moment the generic launches, the whole incentive structure collapses.

Generic companies are fighting back too. Many now include clauses in patent settlement deals that force the brand-name company to delay or even block the launch of an authorized generic. Drug Patent Watch found that 78% of first generic applicants now negotiate these terms. Without them, the risk is too high.

Why This Matters for Patients and the System

On the surface, authorized generics seem like a win for patients. Prices drop faster. More options appear. A 2021 RAND Corporation study showed that when an authorized generic enters alongside the first generic, prices are 15% to 25% lower than when only one generic is on the market.But here’s the hidden cost: if the first generic company loses money, it can’t invest in the next challenge. Smaller generic manufacturers-often the ones most willing to take on risky patents-walk away. They can’t afford to spend $3 million on a lawsuit only to see their profits slashed by their own brand’s move.

The result? Fewer patent challenges. Slower generic entry. More drugs staying expensive longer. The FDA says 78% of new generic approvals in 2022 involved a patent challenge. That’s still high. But the number of first applicants has dropped since 2015. The system is working, but not as intended.

What’s Changing? New Laws and FDA Stance

The debate isn’t over. In 2023, FDA Commissioner Robert Califf told Congress that the current system creates “unintended disincentives for timely generic entry.” He said the agency supports changing the law to stop authorized generics during the 180-day window.Legislation has been introduced multiple times since 2009 to ban this practice. The most recent version, the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, is active in the 118th Congress. If passed, it would make it illegal for brand-name companies to launch an authorized generic during the exclusivity period.

Analysts at Leerink Partners estimate that if this law passes, the value of a successful patent challenge could jump by $150 million to $250 million per drug. That could lead to a 20% to 25% increase in patent challenges. More generics. Lower prices. More innovation in the generic space.

But the brand-name industry isn’t backing down. PhRMA argues that authorized generics help patients get cheaper drugs faster. And they’re not wrong-when both generics are on the shelf, prices fall faster than with just one. But the trade-off is clear: the system that was meant to reward challengers is now rewarding the original monopolist.

How Generic Companies Are Adapting

The smartest generic companies don’t just file ANDAs anymore. They build legal teams, regulatory strategists, and commercial planners into one unit. They map out every possible scenario: What if the patent is invalidated? What if the brand launches an authorized generic? What if the FDA delays approval?They’re also timing their market entry carefully. The 180-day clock doesn’t start when the FDA approves the drug. It starts when they actually ship product to pharmacies. Many companies wait until the last possible moment to launch, hoping to maximize their exclusivity window. But misstep by even a few days? You lose it all.

The FDA reports that 28% of first applicants between 2018 and 2022 lost part of their exclusivity due to procedural errors. That’s not a small number. It’s a warning. This isn’t just about winning a lawsuit-it’s about mastering logistics, timing, and legal fine print.

The Bigger Picture: A System in Transition

Since 1984, the Hatch-Waxman Act has saved U.S. consumers $2.2 trillion in drug costs. That’s real. But the rules were written for a different era. Back then, brand-name companies didn’t make generics. Now, they do. And they’re using that power to reshape the market.The 180-day exclusivity rule was supposed to be a spark for competition. Instead, it’s become a battleground. The winners aren’t always the ones who fought hardest. Sometimes, they’re the ones who played the game best.

For patients, the outcome is still positive-prices are lower than they were. But the path to those savings is getting more complicated. The real question isn’t whether authorized generics help or hurt. It’s whether the system is still fair to the companies that were meant to drive change.

As Congress weighs new laws and the FDA pushes for reform, one thing is clear: the balance between innovation and access is shifting. And the next chapter will determine who gets to play-and who gets left out.

What triggers the 180-day exclusivity period for a generic drug?

The 180-day exclusivity period begins when the first generic applicant starts commercial marketing of the drug. That means the FDA must have approved the application, and the generic product must have been shipped to pharmacies or distributors. Simply receiving approval isn’t enough. The clock only starts when the product is actually on the market.

Can multiple companies share the 180-day exclusivity period?

Yes. Under the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act, if two or more generic companies file substantially complete ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications on the same day, they can share the 180-day exclusivity period. Each gets the full 180 days, but they must all launch before the exclusivity can be triggered for others. This is rare but legally possible.

Why don’t brand-name companies just wait until after the exclusivity ends to launch an authorized generic?

Because waiting defeats the purpose. The brand-name company’s goal isn’t to wait-it’s to capture market share immediately. By launching an authorized generic right away, they prevent the first generic from building customer loyalty or pricing dominance. Even if they sell at a discount, they keep revenue flowing and stop the generic from becoming the default choice.

Are authorized generics the same as counterfeit drugs?

No. Authorized generics are legally manufactured by the original brand-name company or under its license. They use the same active ingredients, same factory, same quality controls. Counterfeit drugs are illegal fakes, often made overseas with incorrect or dangerous ingredients. Authorized generics are fully regulated and approved by the FDA.

What’s the difference between an authorized generic and a regular generic?

A regular generic is made by a different company that proves it’s bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. An authorized generic is made by the brand-name company itself and sold without the brand name. Both are identical in ingredients and effectiveness, but only the authorized generic comes from the original manufacturer.

Is the 180-day exclusivity rule being eliminated?

No. The 180-day exclusivity rule is still active and remains a key part of the Hatch-Waxman Act. What’s under debate is whether brand-name companies should be allowed to launch authorized generics during that period. Proposed legislation aims to restrict that practice, not remove the exclusivity itself.

sean whitfield

December 5, 2025 AT 21:10The whole system is rigged. Brand names own the patents, own the factories, own the FDA lobbyists. They let you win the battle then slide in with the same damn pill in a plain box. This isn't capitalism. It's feudalism with pill bottles.

aditya dixit

December 6, 2025 AT 20:59It's fascinating how legal frameworks designed to promote access end up reinforcing power structures. The 180-day window was meant to empower challengers, but when the incumbent can just rebrand its own product, it becomes a performance of competition rather than its reality. The system rewards strategy over innovation.

Marvin Gordon

December 6, 2025 AT 23:37Let’s be real - if you’re a small generic company betting $3M on a patent challenge, you’re already playing Russian roulette. The authorized generic move isn’t just unfair - it’s a death sentence for the little guys. We need to fix this before the only generics left are made by Big Pharma.

Norene Fulwiler

December 7, 2025 AT 01:24I’ve seen patients cry because they couldn’t afford Humalog. Then I saw them cheer when the generic came out. Then I watched the price drop again when the authorized version hit. It’s messy, but the end result? People get medicine. Maybe the system’s broken, but it’s still saving lives.

William Chin

December 7, 2025 AT 11:12It is imperative to note that the Hatch-Waxman Act, as codified under Title 21 of the United States Code, Section 355(j), does not contain any explicit prohibition against the introduction of authorized generics during the period of exclusivity. Therefore, any legislative intervention must be carefully calibrated to avoid unintended constitutional implications regarding property rights and contractual obligations.

Ada Maklagina

December 8, 2025 AT 19:08so like… the brand makes the generic too? that’s wild. so the guy who sued them is now competing with their own product? that’s like suing your neighbor for stealing your car… then they just drive your exact same car but with no logo. what even is this system

Harry Nguyen

December 9, 2025 AT 07:51Of course the FDA lets them do this. It's all part of the globalist pharmaceutical cabal. The same people who own the patents own the regulators. This isn't about medicine - it's about control. They want you dependent on their branded drugs and only allow generics when it suits their profit margins. Wake up.

James Moore

December 11, 2025 AT 06:26Let us not forget, dear interlocutors, that the very notion of intellectual property - in the context of pharmaceuticals - is inherently contradictory: a life-saving compound, monopolized for profit, then paradoxically permitted to be replicated by the monopolist itself under a different label - a linguistic sleight-of-hand that obscures the fundamental injustice of the system, wherein the legal architecture, crafted in the 1980s, now functions as a gilded cage for the very entities it was meant to constrain.

Kylee Gregory

December 11, 2025 AT 22:21I think the real question is whether we want the system to be fair to companies… or fair to patients. The authorized generics help people get cheaper drugs faster. But if they kill off the next challenger, we lose long-term competition. Maybe we need both - but with guardrails.

Lucy Kavanagh

December 12, 2025 AT 09:41Did you know the same company that makes the brand also owns the FDA’s computer system? I read it on a forum. They can delay approvals just by typing a code. The authorized generic isn’t a loophole - it’s a backdoor. And they’ve been doing this since the 90s. Nobody talks about it because they control the news too.

Chris Brown

December 14, 2025 AT 04:09This is precisely why we cannot continue to tolerate the erosion of American pharmaceutical sovereignty. The fact that foreign-owned conglomerates are permitted to manipulate our regulatory framework - while domestic innovators are systematically undermined - represents a fundamental betrayal of the American worker and the foundational principles of free enterprise.

Stephanie Fiero

December 15, 2025 AT 18:12ok but like… if you’re a small company and you spend 3 million to win a lawsuit… and then the big guy just rolls out his own version… you’re f***ed. like… why even try? someone needs to fix this. i dont care about the politics. people need cheap meds. and the little guys need to be able to win. please. someone help.