Alopecia Areata: Understanding Autoimmune Hair Loss and Modern Treatment Options

Jan, 29 2026

Jan, 29 2026

Alopecia areata isn't just about losing hair-it's about your immune system turning on your own hair follicles. Imagine your body, thinking your hair is a threat, and sending immune cells to attack them. That’s what happens in alopecia areata. It doesn’t care if you’re 8 or 80. It doesn’t care if you’re healthy otherwise. It just shows up, often suddenly, leaving behind smooth, round patches where your hair used to be. These patches are usually the size of a quarter, but they can grow, merge, or even spread to your entire scalp or body. The good news? The follicles aren’t dead. They’re just hibernating. That means regrowth is possible-even after years of loss.

How Alopecia Areata Actually Works

Your hair grows in cycles: anagen (growth), catagen (transition), and telogen (rest). In alopecia areata, the immune system disrupts the anagen phase, forcing follicles into early rest. Histological studies show immune cells, especially CD8+ T cells, cluster around the base of the follicle like a swarm. They don’t destroy the structure-unlike scarring alopecias such as lichen planopilaris-but they shut down growth. This is why hair can come back. The follicle is still there, just silenced.

The condition has several forms. Most people get patchy alopecia areata-small, isolated bald spots. But some develop alopecia totalis (complete scalp loss) or universalis (loss of all body hair, including eyebrows and eyelashes). Ophiasis is another pattern: a band of hair loss wrapping around the sides and back of the head. Then there’s diffuse alopecia areata, where hair thins out evenly, mimicking stress-related shedding. It’s easy to confuse with telogen effluvium, but that’s usually triggered by trauma, illness, or hormones. Alopecia areata? It’s autoimmune. No trigger needed.

It’s Not Just About Hair

Many assume alopecia areata is purely cosmetic. It’s not. Nail changes appear in 10 to 50% of cases: pitting (tiny dents), ridges, or rough, sandpaper-like surfaces. Some people report tingling, itching, or burning on the scalp weeks before hair falls out. And while the condition doesn’t affect physical health, the emotional toll is heavy. Studies from the NIH show alopecia areata causes more quality-of-life damage than psoriasis or eczema. One in three patients reports moderate to severe anxiety. Nearly one in four meets the clinical criteria for depression. On forums like Reddit’s r/alopecia, people share stories of avoiding swimming pools, beaches, or even job interviews because of how they look. One user wrote: “I stopped dating for two years. I felt invisible.”

Treatment Options: What Actually Works

Treatment depends on how much hair you’ve lost and how fast you want results. There’s no cure, but there are tools that help.

Intralesional corticosteroid injections are the most common first step for patchy loss. A dermatologist injects a diluted steroid (like triamcinolone) directly into the bald patches every 4 to 6 weeks. About 60-67% of people see regrowth within 2-3 months. It’s not fun-it stings-but it’s fast and targeted. Side effects? Tiny dents in the skin (atrophy), but those usually fade.

Topical steroids (like 0.1% betamethasone valerate lotion) are less invasive but slower. You apply them daily, often for 6 to 12 months. Success rates? Only 25-30%. It works best for small patches, not widespread loss.

Contact immunotherapy (DPCP) is a more aggressive option. You apply a chemical to your scalp weekly to trigger a controlled allergic reaction. This confuses the immune system and redirects it away from the follicles. It takes 6-12 months. About 30-60% of people respond. But the side effect? Your scalp becomes red, itchy, and flaky-intentionally. Not for everyone.

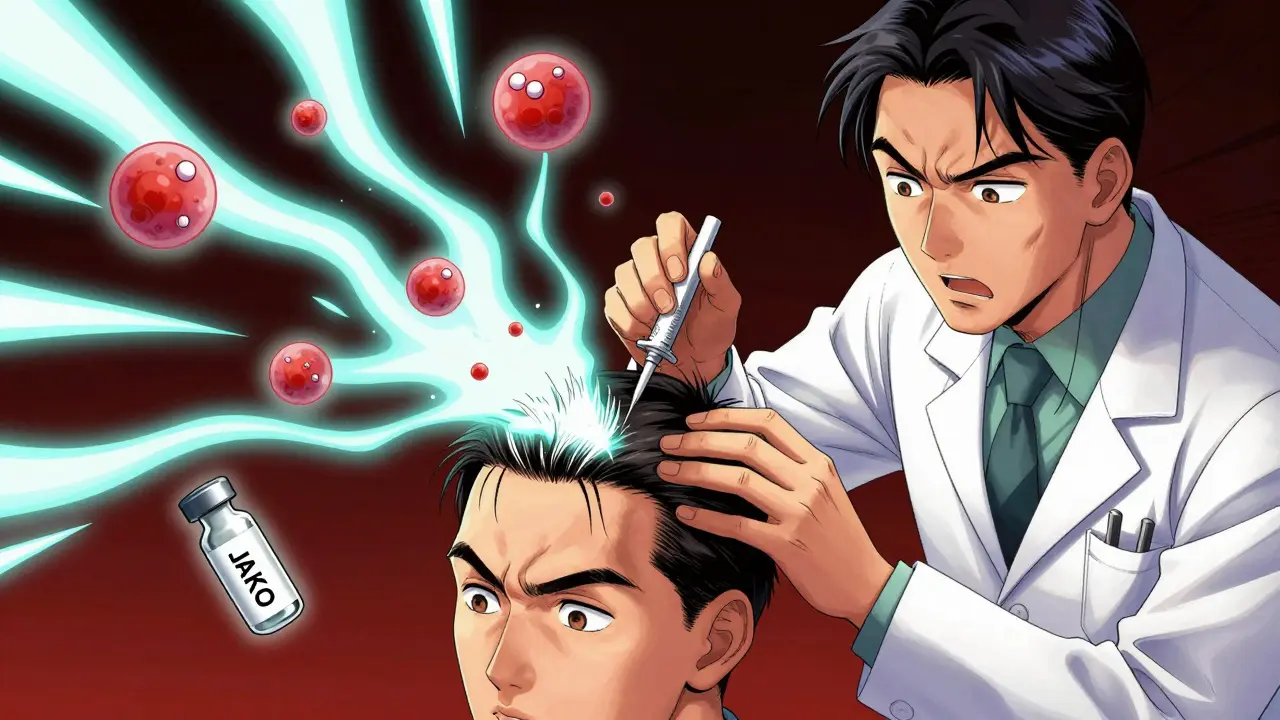

The Game Changer: JAK Inhibitors

In 2022, the FDA approved baricitinib (Olumiant) for severe alopecia areata. It was the first drug approved specifically for this condition. Baricitinib blocks the JAK-STAT pathway-part of the immune signaling chain that attacks hair follicles. In clinical trials, 35.6% of patients regrew 80% of their scalp hair in 36 weeks. That’s huge. In 2023, ritlecitinib got approved too, with similar results: nearly 30% of patients reached 80% regrowth in 24 weeks.

But there’s a catch. These drugs cost $10,000 to $15,000 a month. Insurance often denies coverage unless you’ve tried and failed other treatments. Many patients can’t access them. And even if they work, relapse is common-up to 75% of people lose hair again within a year of stopping the drug. They treat the symptom, not the root cause. Still, for those with total or universalis, they’re the best shot most people have ever had.

What Doesn’t Work (And Why People Keep Trying)

Minoxidil (Rogaine) is often recommended, but it’s not designed for autoimmune loss. In patchy alopecia, it helps maybe 10-15% of people. In totalis or universalis? Almost zero. It works on androgenetic alopecia by prolonging the growth phase. But in alopecia areata, the follicles aren’t stuck in a growth phase-they’re being attacked. Minoxidil can’t fix that.

Essential oils, acupuncture, or gluten-free diets? No strong evidence. Some people swear by them, but controlled studies don’t back them up. The placebo effect is real, and hope is powerful-but it won’t bring hair back if the immune system is still attacking.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. Scientists at Columbia University are developing biomarker panels to predict who will respond to which treatment. The Alopecia Areata Registry, with over 1,800 patients, has linked the condition to specific genes like ULBP3/6, which help the immune system recognize hair follicles as targets. Future treatments may target these exact signals, making therapy more precise and less trial-and-error.

Combination therapies are also being tested: JAK inhibitors plus topical steroids, or light therapy added to immunotherapy. The National Alopecia Areata Foundation predicts a 50% reduction in disease burden by 2030. That’s not a cure-but it’s progress.

Living With It

If you’re newly diagnosed, give yourself time. The first few months are overwhelming. But remember: 80% of people with patchy alopecia regrow hair within a year-even without treatment. Regrowth often starts as fine, white hair. It slowly darkens. One person on a support forum described it: “The hair came back gray first. Then, slowly, my natural color returned. It felt like magic.”

Find support. Join a group. Talk to others who get it. And don’t let anyone tell you it’s “just hair.” It’s your identity, your confidence, your sense of self. The science is catching up. And you’re not alone.

Can alopecia areata be cured?

There is no cure yet. Current treatments can help regrow hair and suppress the immune attack, but they don’t fix the underlying autoimmune dysfunction. Many people experience regrowth, but relapses are common, especially after stopping medication. Research is focused on long-term solutions, including personalized therapies.

Is alopecia areata contagious?

No. Alopecia areata is an autoimmune condition, not an infection. You cannot catch it from someone else, nor can you spread it through touch, hair, or bodily fluids. It’s caused by your own immune system mistakenly attacking hair follicles.

Can stress cause alopecia areata?

Stress doesn’t cause alopecia areata, but it can trigger it in people who are genetically predisposed. The condition is rooted in genetics and immune dysfunction. Many people report a stressful event before hair loss began, but that’s a trigger-not the root cause. Managing stress won’t cure it, but it may help reduce flare-ups.

Do JAK inhibitors work for everyone?

No. In clinical trials, about 35% of patients achieved 80% scalp regrowth with baricitinib or ritlecitinib. Others saw partial regrowth, and some saw no change. Response varies based on genetics, disease duration, and severity. People with long-standing or universalis hair loss tend to respond less predictably. These drugs are not a guaranteed solution.

Will my hair grow back naturally?

Yes, for many. About 80% of people with limited patchy alopecia regrow their hair within a year without treatment. Regrowth often starts as fine, white hairs that gradually regain color. But if you have extensive loss-like totalis or universalis-spontaneous regrowth is rare, happening in only about 10% of cases. Monitoring and early treatment improve outcomes.

Can children get alopecia areata?

Yes. About half of all cases begin before age 40, and many start in childhood. Children can develop any form, including totalis or universalis. Treatment options are similar but adjusted for age. Corticosteroid injections and topical therapies are commonly used. JAK inhibitors are now approved for adolescents 12 and older in some countries, including the U.S.

Are there side effects from treatments?

Yes. Corticosteroid injections can cause skin thinning or dents at the injection site. Topical steroids may cause redness or irritation. DPCP causes intentional allergic dermatitis-red, itchy skin-which some find hard to tolerate. JAK inhibitors carry risks like increased infection, elevated cholesterol, and blood cell changes. These are monitored by doctors, but they require regular blood tests and careful management.

How long does it take to see results from treatment?

It varies. Injections show results in 2-3 months. Topical treatments take 6-12 months. Contact immunotherapy and JAK inhibitors usually take 3-6 months before noticeable regrowth. Patience is key. Hair grows slowly-about half an inch per month. Even if you don’t see change after a month, don’t give up too soon.

Niamh Trihy

January 30, 2026 AT 03:17Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest explanations of alopecia areata I’ve ever read. The breakdown of immune cell behavior around follicles? Spot on. I’ve been following the JAK inhibitor trials since 2021, and seeing baricitinib approved was a watershed moment. Not a cure, but finally a real tool. Keep sharing this kind of stuff.

KATHRYN JOHNSON

January 30, 2026 AT 05:26This article is scientifically accurate and meticulously referenced. The distinction between autoimmune disruption and mechanical damage to follicles is critical. Too many online sources conflate alopecia areata with telogen effluvium. This deserves to be cited in medical forums.

Sazzy De

January 30, 2026 AT 23:18My sister lost all her hair at 19. Took 7 years for it to come back. Gray at first. Then brown. Still don’t wear hats. Still don’t care.

Diana Dougan

February 1, 2026 AT 00:56so jaks cost 15k a month?? and insurance says no unless you try minoxidil first?? lmao. theyre literally treating symptoms like its 1995. why dont they just give the drug to everyone and save the therapy bills??

Holly Robin

February 2, 2026 AT 11:16EVERYONE knows the real cause is 5G + glyphosate + vaccines. The immune system isn’t attacking hair follicles-it’s reacting to corporate toxins. That’s why it’s worse in cities. That’s why kids are getting it now. The FDA approves drugs to keep you dependent, not healed. I’ve been using copper bracelets and moon water since 2020. My eyebrows grew back. Coincidence? I think not.

Natasha Plebani

February 3, 2026 AT 14:59The JAK-STAT pathway’s involvement in alopecia areata represents a paradigm shift from symptomatic management to pathway-specific immunomodulation. However, the epistemic gap remains: we still lack a causal model linking ULBP3/6 polymorphisms to follicular autoantigen presentation. The current pharmacological interventions are palliative proxies for a deeper ontological malfunction-what we’re observing is not merely immune dysregulation, but a failure of self-tolerance mechanisms that evolved over millennia to protect integumentary integrity. Until we map the thymic selection defects in CD8+ T-cell repertoires, we’re essentially treating the shadow, not the object casting it.

Blair Kelly

February 3, 2026 AT 19:24They approved a $15,000/month drug for a condition that 80% of people recover from naturally? That’s not medicine-that’s pharmaceutical theater. They’re monetizing insecurity. Meanwhile, people with real chronic pain get denied opioids. This is capitalism dressed in lab coats.

Gaurav Meena

February 4, 2026 AT 23:27As someone from India who grew up with relatives saying 'it's just bad luck' or 'stop worrying so much'-this article changed everything. My cousin had totalis at 12. We thought it was karma. Now I know it's biology. Thank you for writing this with dignity. I'm sharing it with every family member who still says 'cover your head, you'll get better.'

Shubham Dixit

February 5, 2026 AT 20:43Look, I respect the science here, but let’s be real-this isn’t just about hair. It’s about identity. In India, a man without hair is seen as weak, old, or broken. Women? Even worse. You think a girl with no eyebrows can walk into a marriage meeting? No. So yes, JAK inhibitors are expensive. Yes, insurance is a joke. But if a drug can restore dignity, then it’s not just treatment-it’s justice. And if Big Pharma profits? Let them. They’re not paying for my daughter’s confidence. I am. And I’d pay ten times more.

Diksha Srivastava

February 7, 2026 AT 11:36I just want to say to anyone reading this who’s scared: you’re not broken. Your hair doesn’t define you. I lost mine at 24. I wore wigs. I cried in the shower. Then I started painting. I started speaking at support groups. Now I run a nonprofit. The hair came back slowly-gray, then soft, then mine. But even if it never did? I’m still here. Still loud. Still loved. This isn’t the end of your story. It’s the beginning of a new chapter. And you? You’re already winning.

Jason Xin

February 9, 2026 AT 01:18Interesting how everyone’s focused on the drugs, but nobody talks about the fact that 80% of patchy cases resolve on their own. Maybe the real breakthrough is acceptance-not medication. We treat hair loss like a medical emergency, but sometimes it’s just… biology doing its thing.

Kelly Weinhold

February 9, 2026 AT 04:43Jason’s right. I lost hair at 30. Took 18 months to grow back. I didn’t use anything. Just stopped checking mirrors every hour. Started hiking. Started saying 'yes' to things I used to avoid. Hair came back. Not perfect. But I didn’t need it to be. The real healing wasn’t in the cream or the shot-it was in letting go of the shame. I’m not saying don’t treat it. Just don’t let it own you.

Lily Steele

February 10, 2026 AT 06:14my dermatologist said if i dont see results in 6 months just stop the jaks and enjoy the quiet. i did. no hair. no stress. no more mirrors. i feel better than ever. who knew the cure was doing nothing?

Rohit Kumar

February 11, 2026 AT 04:04There’s a deeper truth here. In ancient India, we had no word for alopecia areata. We called it 'keshahara'-the loss of grace. We didn’t cure it. We honored it. Monks with no hair were revered. Today, we chase hair like it’s a trophy. Maybe the real treatment isn’t a drug-it’s a shift in how we see ourselves. Not as broken, but as beings who carry more than skin and follicles.