disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

When working with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, medications that slow or stop joint damage caused by autoimmune inflammation. Also known as DMARDs, they are a cornerstone of modern rheumatology and are prescribed to keep joint erosion at bay.

Rheumatoid arthritis, a chronic inflammatory disease that attacks synovial joints is the condition most people associate with DMARD therapy. Without treatment, the immune system's attack can lead to irreversible cartilage loss, deformities, and disability. DMARDs intervene early to modify that disease course, turning a progressive illness into a manageable one.

Key Types of DMARDs

The DMARD family splits into two major groups. Conventional synthetic DMARDs, small‑molecule drugs such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine and leflunomide have been used for decades and work by broadly suppressing immune activity. Biologic DMARDs, protein‑based agents that target specific cytokines or immune cells include TNF inhibitors, IL‑6 blockers, and B‑cell depleters. Both groups aim to reduce inflammation, but they differ in delivery (oral vs injection/infusion) and precision of action.

One semantic link: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs encompass conventional synthetic DMARDs and biologic DMARDs. Another: DMARDs require regular monitoring of blood counts and liver function to catch side effects early. A third: using DMARDs improves disease activity scores, which doctors use to decide if the therapy is working.

Safety is a big part of the conversation. Conventional synthetic DMARDs often cause liver enzyme elevations, nausea, or mouth sores, while biologics can increase infection risk and, rarely, trigger auto‑immune events. Because of these risks, rheumatologists order baseline labs and repeat them every few weeks to months, adjusting doses or switching agents as needed.

Although rheumatoid arthritis dominates the conversation, DMARDs also treat other inflammatory conditions. Psoriatic arthritis, a disease that combines skin psoriasis with joint inflammation and ankylosing spondylitis, a spine‑focused arthritis both respond to the same drug classes. This cross‑application shows how DMARDs address the underlying immune dysregulation rather than a single joint location.

2025 brought a wave of new oral agents called JAK inhibitors. These small molecules sit between conventional synthetics and biologics: they’re taken by mouth but target specific signaling pathways inside immune cells. Early data suggest they work fast, have manageable side‑effect profiles, and can be combined with methotrexate for added benefit. As more heads-up trials finish, JAK inhibitors may become a third pillar alongside the traditional two.

For patients, the practical side matters most. Sticking to a weekly methotrexate dose, keeping a calendar for lab visits, and reporting any unusual infections are simple habits that keep therapy safe. Lifestyle tweaks—like limiting alcohol, staying hydrated, and protecting the skin from sun—can cut down side‑effects. If a biologic causes injection site pain, nurses can teach alternate sites or use auto‑injectors to ease the process.

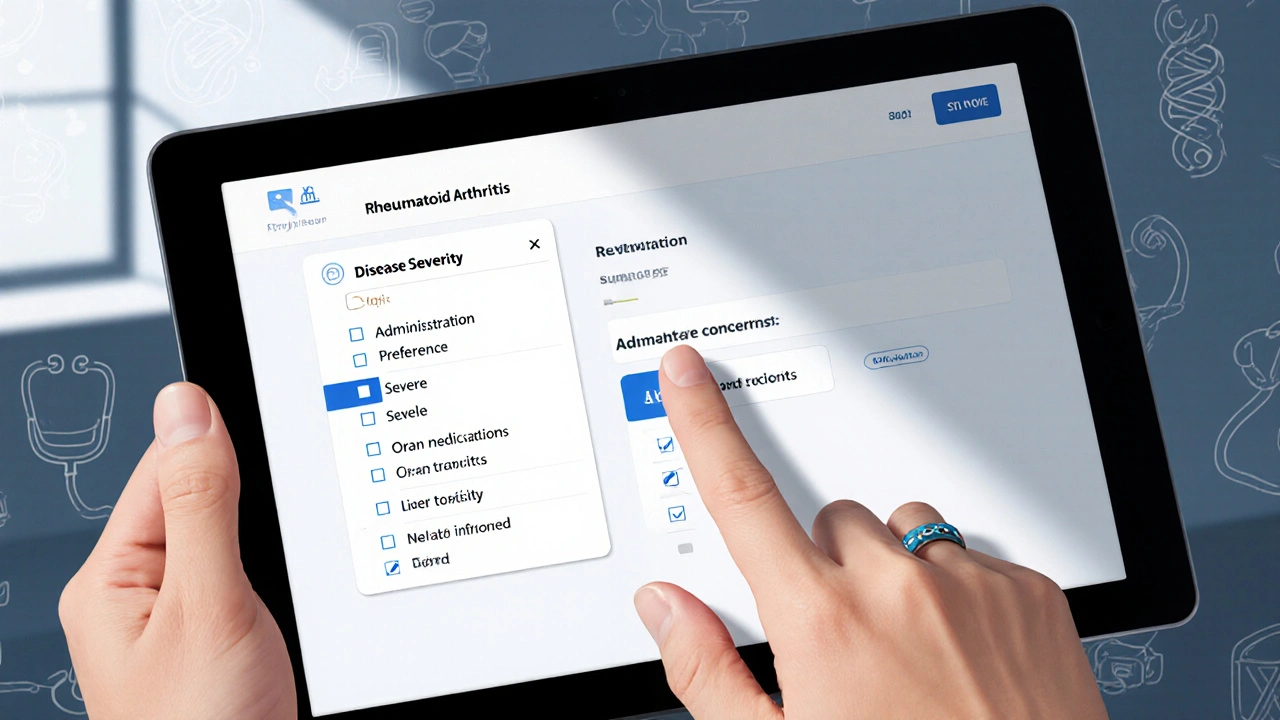

From the clinician’s viewpoint, choosing a DMARD involves balancing disease severity, comorbidities, patient preferences, and cost. Biologics tend to be pricier, but insurance coverage and patient assistance programs have widened access. Some doctors start patients on methotrexate, then “step‑up” to a biologic if the disease activity score stays high after three months. Others opt for early aggressive therapy if imaging shows rapid joint erosion.

Below you’ll find a curated list of articles that dive deeper into each of these topics. Whether you need a side‑by‑side comparison of biologic options, a guide to safe lab monitoring, or the latest outlook on JAK inhibitors, the posts below are organized to give you quick, actionable insights.